Get a job. –

Every so often someone contacts me to ask for advice about quitting a day job and going into furniture making as a full-time endeavor. They’ve taken some classes and built some pieces — sometimes eye-poppingly impressive ones — on their own time. Some have had paid commissions and amassed a months’-long backlog for more paid work that leads them to think it’s time to take the plunge. Inundated by images of other woodworkers on social media — usually without any indication as to which ones are making furniture for a living, as distinct from in their spare time, or those who work at it full-time with support from a well-employed partner* — the people who contact me with this deeply existential inquiry seem to feel they’re missing out on the #selfemployedandlovingit lifestyle.

I invariably ask about their circumstances. Do they live alone? Have a family to support? Is there a partner with a regular source of income and benefits such as health insurance (which, depending on your age and other factors, can easily cost more per month than a mortgage)? I also point out that the good times can’t be relied upon to last; when your household income depends entirely on making furniture — a product that most people consider desirable, rather than necessary — economic downturns can be devastating.**

But self-employment is not the only option. In the past month I’ve heard from three furniture makers who are looking to hire.

Running my own furniture business was my dream, too, when I completed the basic City & Guilds furniture training in 1980. Luckily for me, I was disabused of that dream by my first woodworking employer, Roy Griffiths, who paid me to learn what full-time professional woodworking might mean. (I say “might mean” by way of acknowledging that every woodworker’s situation is different.) I followed that experience with work in another English workshop, then came back to the States and learned a whole new set of techniques and lessons about the business side of furniture making at Wall-Goldfinger in the late 1980s. To be clear, at no time during those years did I view myself as jumping from one employer to another in order to learn; I’m portraying my employment experiences in terms of learning here because I now have a sense of the invaluable education I obtained by working for others.

If you’re contemplating going pro, consider the traditional route — that of working for an established woodworking business. You will learn a ton of new techniques (trust me; every shop I’ve worked in has done things differently) in addition to gaining insight into what making furniture or cabinets on a daily basis really entails. You will also learn about the business of woodworking in the most real-world way. And you will be paid for this learning!

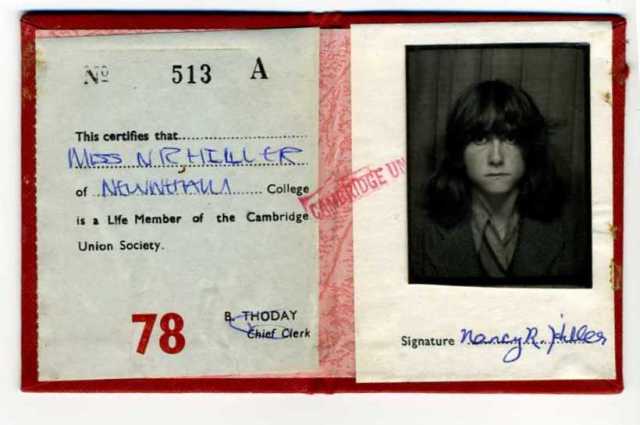

— Nancy Hiller, author of Making Things Work

*Save your outraged comments. I mean no disparagement to anyone. I’m simply pointing out that curated images on social media lead to inferences that in many cases do not match the underlying reality.

**Stay tuned for my interview with Aimé Ontario Fraser, who speaks poignantly about her own experience during the Great Recession. Also check out Paul Downs’s book, which is an excellent read.