Wooden Plates our Forefathers Used –

GOLD and silver; earthenware, pewter and china, have, in different times and under different circumstances been used for plates. Our own forefathers relied on wood. From the earliest times to days well within living memory the wooden platter, the bowl, the drinking vessel, the spoon and even the knife and fork lay on the rude trestle table for daily meals.

Many countrymen recall the wooden implements of childhood memory, and the writer himself remembers the flattened wood porridge plate and the coarse surfaced bowl of the wooden spoon.

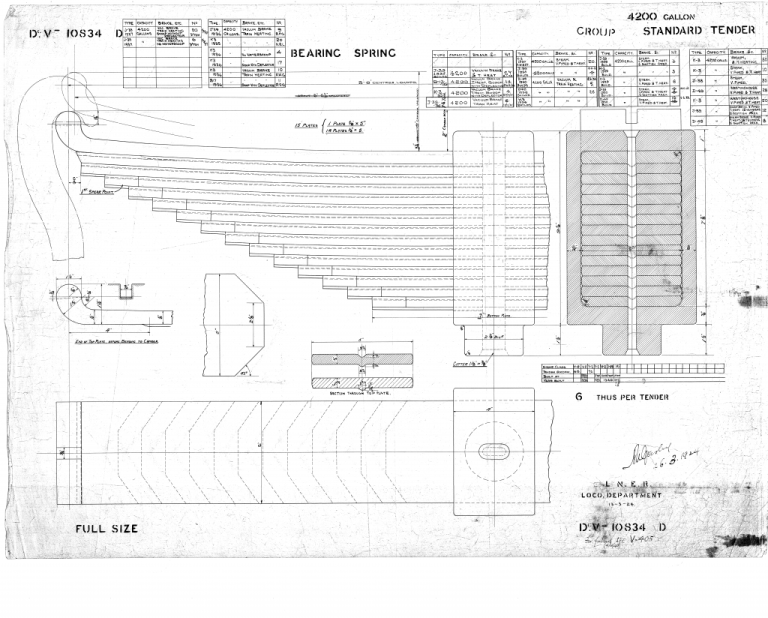

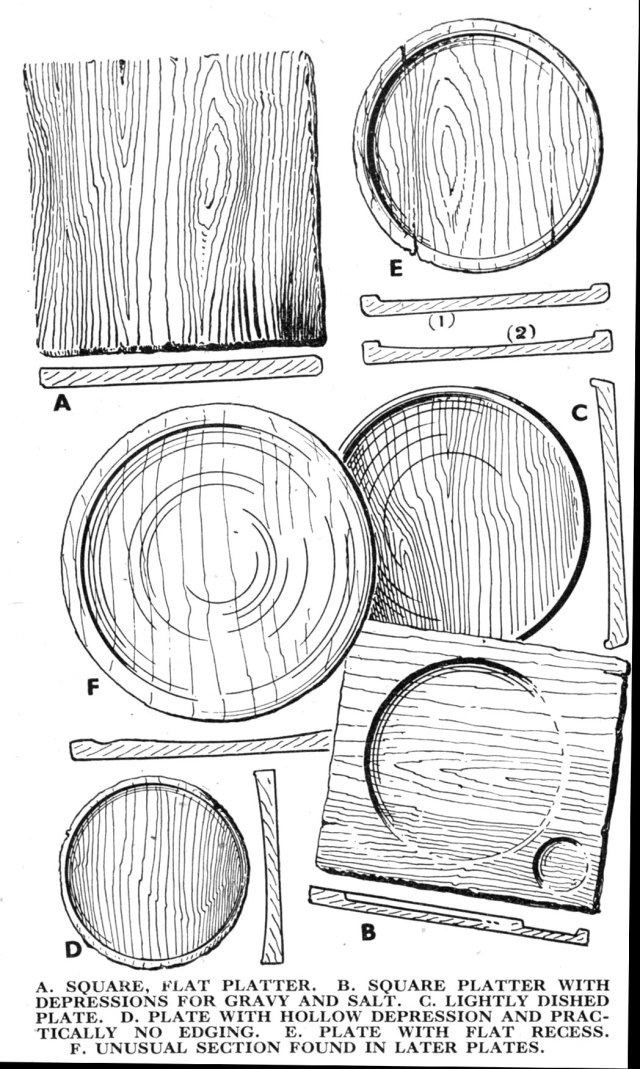

Until early Tudor times the wooden platter was almost universal. Then, and for long before (indeed, too, for long afterwards) the common table was found in every home, the humblest stable boy “supping with his titled lord.” His only dish might be a square wooden platter such as (A) in the illustration, whilst for anything approaching an implement such as a knife or fork the fingers and teeth were sufficiently dexterous for the purpose. Later, as ideas of refinement crept in, superior wooden vessels were found at the head of the table, whilst cruder ones were provided for retainers at the lower end.

Dogs (many of them) did much of the cleaning up. When wooden knives, forks and spoons, rather more difficult to fashion, came into general use it was the custom of visitors to bring their own with them.

The gradual development of the plate is interesting, although its various forms cannot be traced with absolute accuracy. Naturally they vary in different countries. Quite obviously, the earliest plate was a mere platter – a roughly squared board (as A), perhaps about 8 ins. To 10 ins., with its upper surface smoothed for reasonably comfortable use. The first innovation was a shallow circular sinking in the board as at (B), the depression preventing the overflow of gravy. The addition of a smaller sinking at one corner for salt came later.

Larger flat trenchers from which the food was handed round the table took a rectangular form and might be 18 ins. by 12 ins. or more. These would have rounded corners, whilst, after dishing came to be introduced, they frequently took an oval or square-oval form. A deeper cavity at one end to take the gravy has in pewter and earthenware dishes, continued to the present day.

The dishing, or hollowing, of platters gradually brought in the circular form, of which (C) is the earliest. At first the centre of the plate was kept flat as at E, 1), but hollows such as those at (C),

(D) and (E, 2) became more frequent. The section at (F) is a later development. These circular plates might be from 6½ in. to 9 in. in diameter, but often for special purposes exceeded this size. Note that at (D) there is practically no rim. At (C) the rim is hardly more than a bead, whilst at (E) and (F) the rims are much wider. As craftsmen gained skill in turning, the bowls of these plates became deeper and better suited to their purpose; delicately moulded rims appeared, and, as the under surfaces were worked to a pleasing and useful section, the plate became lighter to handle. Sycamore was the most generally favoured wood for dishes in which cooked food was to be placed. For bread and uncooked fruit, beech plates were more common.

— From The Woodworker magazine, edited by Charles H. Hayward