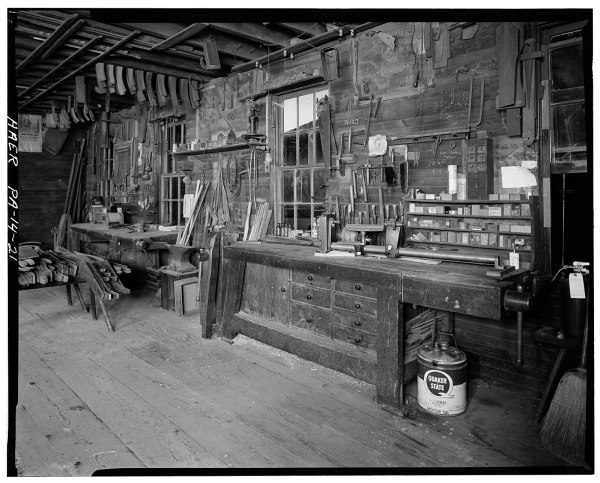

Keeping Tools –

Keep your tools handy and in good condition. This applies everywhere, and in every place, from the cobbler on the bench to the greatest mechanical establishment in the world, and in no place is it more necessary than in wood-working concerns. Every tool should have its exact place as much as a note in an organ, and should always be returned to its place when not in use.

Having a chest, or any receptacle with a lot of tools thrown into it promiscuously, is just as bad as putting the notes into an organ without regard to their proper place. If a man wants a wrench, chisel or hammer, it’s somewhere in the box or chest, or somewhere else, and the search begins. Sometimes it is found—perhaps sharp, perhaps dull, maybe broken; and by the time it is found he has spent time enough to pay for several tools of the kind wanted.

The habit of throwing every tool down, any how, in any way, or any place, is one of the most detestable habits a man can possibly get into. It is only a matter of habit to correct this. Make it an inflexible end of your life to “have a place for everything and everything in its place.”

It may take a moment more to lay a tool up carefully after using, but the time is more than equalized when you want to use it again, and so it is time saved. Habits, either good or bad, go a long ways in their influence on men’s lives, and it is far better to establish and firmly maintain a good habit, even though that habit has no special bearing on the moral character; yet, habits all have their influence.

Keeping tools in good order, and ready for use, is as necessary as keeping them in their proper place. To take up a dull saw, or dull chisel, and try to do any kind of work with it, is worse than pulling a boat with a broom, and it all comes from just the same source as throwing down tools carelessly—habit. Nothing more nor less. To say you have no time to sharpen is worse than outright lying, for if you have time to use a dull tool, you have time to put it in good order.

I once knew an old farmer who, when he saw his hired man come limping along, said, “What is the matter, John; are you hurt?” “No,” said John, “I’ve only got something in my boot and I’ve not got time to get it out.” “Well, John, here’s your pay. I don’t want a man to work for me that has not got time to take his boot off when it hurts him. A man like that would not take care of my horses if they got hurt, because he wouldn’t have time.”

Cuir

The Wood-Worker – March, 1888

—Jeff Burks