The Art of Knuckle Grinding –

Unless tools are well and keenly sharpened, satisfactory work is impossible. Much of the difference between professional and amateur work arises from the bluntness of the tools of the latter. No mortised and tenoned joint can be made to fit closely if the work is not cleanly cut by a sharp chisel; and planed surfaces, if badly done, are more unsightly than if left rough from the saw.

Various contrivances for holding a tool securely during the operation of grinding have been devised, and I may notice the undeniable fact that I never saw them in use among workmen. It is indeed a mistake to rely upon what are, at best, questionable devices, when, by patient practice, we can gain that skill which will not fail us in the time of need. A simple toolrest—a mere bar of iron parallel to the face of the stone, may be a help in steadying a tool; but even this is seldom to be seen in the carpenter’s shop, its absence proving that it is not a necessity.

But there are necessaries in tool grinding always to be found among practical mechanics which are too often wanting among amateurs, and these are patience and determination. Grinding tools is a laborious and disagreeable operation, which is sure to be avoided as long as possible, and is terribly scamped by amateurs when it can be no longer delayed. If, however, it must be done, let it be done thoroughly, or the labour bestowed will be entirely thrown away.

The main object of grinding is to produce a bevel on one side or both of a tool blade, in order to reduce the metal to a thin cutting edge. This bevel must not be too short, or the angle of edge will not be small enough; it should, therefore, be carried well up the blade, so as to present a broad surface. In a perfectly new chisel or plane the grinding will be found insufficient, because tools with keen edges cannot be kept in stock. They would endanger the hands of the shopmen, and would also get damaged and notched by contact with each other.

Hence a new tool must be ground before use, and the bevel already formed extended. But if you examine the surface that has been ground by the workman you will see how flat and even it is; the upper part forms a straight line across the blade, and the whole is quite flat, even, and true. This is what you have to aim at, and when you commence to be your own grinder you will be disgusted to notice how you have spoilt the even bevel which the tool once had. Instead of one bevel you have produced several, lying at all sorts of angles with each other. This arises from not holding the tool steadily upon the stone.

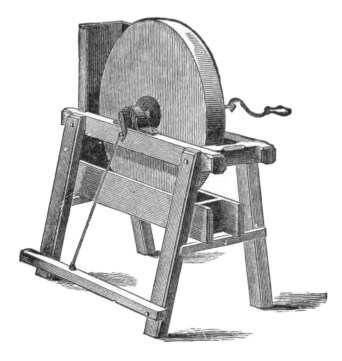

To get an even bevel the stone must itself be absolutely true, and not wobble from side to side. You can now buy, at a comparatively low price, excellent grindstones turned quite true upon the face, and worked by a treadle; or you can buy, for a few shillings, an unmounted stone, and fit it up, or have a frame made by a carpenter. In either case have it fitted with a treadle, so as to render yourself independent of assistance; and have a nice fine Bilstone, not a Yorkshire grit, which is more fit for coarse work.

I do not think you will gain by buying the small 5in. or 6in. stones now to be had in metal troughs; they do for chisels and turning tools, but are of no use when an axe or plane iron has to be sharpened. A stone 18in. diameter to 2ft. at the most will do all you need. Probably the former size will suffice, but one less than 18in. has hardly weight enough to make it act as its own fly wheel.

Any small stone to be used for plane irons would need a fly wheel on the same axis to give it the necessary impetus, and such a fly wheel would be often found terribly in the way of the arms and elbows. Moreover, you require a tolerably large stone to produce a sufficiently flat bevel, although a slightly hollow one is no great disadvantage. Have, therefore, a good sized stone nicely mounted as the first essential of good work, and having once obtained such use it well.

Now, to use it well is not to allow one side to lie constantly in the water, which will rapidly soften it, and of course cause it to wear faster than the other, thus rendering the stone untrue. Hence, although you need a water trough to catch the water from the drip-can placed above it, there should be a pipe below to carry it off at once into a bucket or drain, which will also remove the muddy silt that is so often allowed to accumulate in the trough until it well nigh prevents the stone turning round. This again is an essential lesson in cleanliness, which must by no means be neglected in a mechanic’s workshop.

Supposing the grindstone thus mounted to run truly, the next consideration is the way to hold the tool. This must be held rigidly in one place, i.e., at the same level, merely being traversed from side to side to prevent it wearing the stone unevenly, especially if the tool be a narrow one like a mortice chisel, which, if held quite still, will cut a channel, and spoil the face of the stone.

Now, if you grind with the stone running away from the edge of the tool, and do not hold it firmly in position, the former will seem to lay hold of it and drag it away to a higher position. This is what you have to resist, and the best way to do so is to hold the elbows firmly against the sides, which affords a very secure grip indeed.

This is not the orthodox way to run the stone, which should always turn towards the edge of the tool, although it would naturally appear the wrong way to use it. But to turn the other way is to produce a wire edge, which is difficult to remove, and no workman would grind thus, unless it were a narrow tool, liable to groove the stone.

The tendency of the stone, therefore, will generally be to drag down the tool, the danger being that if you let it do so it will dig in and cut out a notch, tumble into the trough, and give you a practical illustration of the art of knuckle grinding. But it is easier to resist this tendency to drag the tool towards you, and you will soon learn to hold it steadily and level (for here is another difficulty). If not held level and square across the stone, the bevel will be broader at one part than the other, and the edge of the tool will slant, so that (if a plane iron) it cannot be placed true with the sole of the tool.

If only for a moment you let the tool have its own way, you will find that a fresh surface has been ground out of the general plane. Thus it is evident that to grind a tool well needs practice, and a pair of good strong arms, and the art cannot be learnt in a day. Being moreover a tiresome job, one naturally feels disposed to shirk it, which means grinding a smaller bevel, and, of course, obtaining a blunter edge.

In addition to the fault of unevenness of bevel, a very common one is a rounded surface instead of a flat or hollow one. This results generally from paying more attention to the edge than to the entire bevel. Let the extreme edge take care of itself, and concentrate the attention upon the flat surface of the bevel, especially the middle of it, and grind till you observe that the edge has actually come down upon the face of the stone, proving the work done.

All success depends upon the rigid hold upon the tool keeping it steadily at one level. The pressure need not be excessive, and, although it may take longer, the labour involved will be less if only a moderate pressure is kept up. Sway the body from side to side (not the arms alone) in order to traverse the tool across the face of the stone, and a little careful practice will insure success. After awhile it will be found easy to grind with the arms more free; but I have found, practically, the way I have described the surest and safest for beginners.

To test the correctness of the edge, try it with a square, especially if it be a plane iron, and if it be ground slanting instead of square to the sides, you must set to work again. Knowing this penalty to be in prospect for careless work, you will be wise to test the tool once or twice as you proceed.

Assuming that the grinding is satisfactory, you now have to set the edge on an oilstone to make it smooth and keen. In this operation, which looks a deal easier than it is, the danger of rounding the bevel steps in. What you have to aim at is to produce a new narrow, but decided, bevel at a slightly greater angle than that obtained by grinding, and you must not round it off into the other.

If you are a novice your success is highly problematical. I must pre-suppose a good oilstone, Arkansas or Washita, the first being the best, level and clean, and with a few drops of clean oil or paraffin upon it. Set it on the bench with one end towards you, or nearly so, as the movement of the tool will be to and fro from end to end of the stone. Grip the iron firmly in the left hand, and place the other hand over it, grasping it, but with the first three fingers pointing downwards towards the edge of the tool—a position that gives a good steady hold—and laying the iron upon the stone at a rather larger angle than that of the bevel, rub it steadily a few times to and fro.

By “larger angle” I mean a little more upright than lying flat upon the bevel. In pushing the iron from you, it is necessary to raise it to a slightly more upright position, and to depress it as you draw it back again, because the natural movement of the arms, unless thus counteracted, would lower the iron as it recedes, and thus tend to round off the bevel—the error already alluded to.

The movement will become quite easy and natural by and by, when once you know what you have to do, but it takes practice to move the arms thus horizontally, and their natural tendency is to move in an arc of a circle, of which the shoulder joints form, of course, the centre. A rounded bevel will cut, but it is not to be compared with a flat one, and is, besides, very unworkmanlike.

I shall not enter into a question here as to the proper sizes of tool angles. Let it suffice for the present to remark that for deal and other soft and fibrous wood the tools cannot be too keen, and that, therefore, the bevel must be large, i.e., the tool must be ground some distance up the blade, while for hard wood it need not be quite so far ground, but must be kept sharp even at a larger angle.

Before putting the newly-ground iron in the plane, lay it quite flat upon its back on the oilstone, and pass it once or twice up and down to remove any slight burr thrown up by the stone. The top or break iron is placed low down or the contrary, according to whether the plane is to be used for rough or fine work. In a jack plane it is placed about ⅛in. from the edge, but in a trying plane or smoothing plane it must leave only a very narrow bit of the cutting iron exposed. The object of this break iron, as it is called, is to bend up the shavings sharply, so as to insure their being cut off and not split from the surface of the board.

Put the irons thus clamped together into the stock with the bevel of the cutting edge below, and placing the wedge in position, tap it in lightly. Then turn the plane upside down, and take a glance along the sole (the eye at the front or forward edge), and you will see the black line of the iron, a mere line if the plane is set finely. If it projects too far, a tap with the mallet on the top or back of the stock will cause it to withdraw if you have only wedged it lightly. If the iron does not project at all, you may give it a tap to send it forward, or a blow or two on the front end of the plane. When just visible and true to the level of the sole, another tap on the wedge will secure it—but never drive the wedge too tight, or you will split out the sides and spoil the plane.

The method of grinding other tools, as chisels, is so precisely similar, as well as the mode of setting them on the oilstone, that I need not extend this chapter to treat of them separately. Practice is all that is required to make anyone a good tool sharpener.

James Lukin

Toys and Toymaking – London, 1882

—Jeff Burks